Week 8: Spam

This week was titled “messaging security”, but it is actually all about spam detection.

Let’s start with some basic terminology.

-

Spam is an unwanted email; ham is anything that isn’t spam. The basic goal of spam detection is to classify emails as either spam or ham.

-

A spamtrap is an email address which receives nothing but spam. This can either be an email server set up specifically for this purpose, which has never been used for legitimate email, or it can be a formerly valid email address which was discontinued. In the latter case, the retired address is usually set to hard bounce for six months, after which it can be assumed that anything sent to it is spam.

-

Snowshoe spam is spam with a light footprint. Botnets used to send spam out as fast as they could; once a machine got infected, it would start sending out spam day and night. This was easy to detect and block, so the started sending at a low rate, blending in with normal traffic patterns. This, it turns out, is very hard to detect.

-

RBL is a realtime blackhole list. More on that next.

Blocking spam

A lot of spam blocking actually occurs at the network or SMTP level, long before the email hits your inbox (or spam folder).

One of the main weapons against spam is the RBL, Realtime Blackhole List. This is simply a blacklist of IPs which are known to be sending spam.

This is great because it blocks spam at the network level, which is low-resource. You simply configure your routers to block all packets coming from IPs on the RBL.

The downside is that IP addresses often change, and what was a spam IP yesterday might be a legitimate IP today, or vice versa. To keep up with the changes, you have to subscribe to a RBL from a company like Spamhaus, who reportedly owns most of the RBL market.

One of the ways Spamhaus gets the info for their RBLs is with PBLs - policy block lists. When an ISP allocateds a range of dynamic IPs, they tell Spamhaus and that range goes on a blocklist (consumers not allowed to run their own mail servers, you see.)

One step up from the network layer is the application layer.

SMTP (Simple Mail Transport Protocol) is the protocol which governs how mail is moved between servers. Email is a hop-by-hop business: you send your email to an outgoing SMTP server; it stores it and forwards it to another email server; and so on. Eventually it gets to its destination and you retrieve it from the server using POP3 or IMAP.

When an SMTP server wants to block a spam messages, it simply responds to the request

with a 554 Denied code, which tells the sender to bugger off and not come back.

It doesn’t generate a bounce message or anything,

just drops the message on the floor and tells the sender to go away.

This is the strongest response.

There are lesser error code that can be used for lower confidence spam,

like 451 Temporary Error, which is also used for things like rate limits.

The server could also store the message for later analysis,

but if it later decides to block the message it would have to send a bounce message.

Or it could just accept the message and let the recipient deal with it. These are the messages that end up in your spam filter.

It’s better to stop spam earlier, though.

For spam blocking to work at this level, classification has to be quick. McAfee’s spam classifier aims to work in 20ms or less, for example.

Detecting spam

There are two general methods for detecting spam: rule-based, and Bayesian.

Rule-based

The rule-based approach is similar to what we discussed in week 3 for detecting viruses: manually-written rules which try to match strings in an email against known phrases used in spam. Like AV rules, these can either be fixed strings or regexs.

We can also look at features of the email other than its contents; for example, does the email have an attachment? does it contain a url? who is the sender?

We can construct even stronger rules by combining these sorts of features into “meta rules”; for example, if an email comes from Pfizer, has a subject containing “buy viagra”, contains an image (any image), contains a url (any url), and does not have attachment, then that’s spam.

Bayesian

That’s great but who wants to create a bunch of spam rules by hand? Nobody, that’s who.

Enter Bayes.

I believe the Bayesian approach to spam filtering was first described by Paul Graham in A Plan for Spam, an essay published in August 2002.

The basic idea is to use a statistical approach to automatically find words in the email that are highly associated with spam, instead of trying to find them by hand.

This idea became the SpamBayes project, an open-source Python program that used Bayesian filtering to flag spam. It enjoyed a few years of success, but it is now unmaintained. Its last release was in 2008.

Nowadays spammers have gotten more sophisticated and the best filters are run by large corporations like Google who can use a huge database of spam messages to train more sophisticated machine learning modules.

Just like in URL classification last week, it is more important to have few false positives than to catch all spam messages. However, note that because of the volume of spam

- several billion spam messages are sent every day - if your spam filter is 99% accurate then that 1% represents more than 10 million spam messages that get through.

In which I ignore the lesson plan and do something else

We were supposed to come up with some home-grown rules for flagging spam messages, but since I already created a rule-based approach for URL classification last week so I decided to try the Bayesian approach this time.

We are interested in computing:

P(spam | word)

Which is read as “the probability that a message is spam, given that it contains the word word”.

Per Bayes’ Theorem,

P(spam | word) = P(word | spam) / P(spam)

This says that the probability that message is spam (given that it contains some word) is equal to the probability that that word appears in a spam message, divided by the overall probability that a message is spam.

(P(spam) represents our prior probability that we believe the message is spam, and P(spam|word) is the posterior probability after observing that it contains word.

We’ll assume P(spam) is .5 even though the actual distribution is closer .85, to avoid biasing the algorithm towards classifying messages as spam.)

That’s just the probability after observing a single word. What we really want is to compute the probability after seeing every word in the message.

P(spam | word1, word2, word3, ...)

If we assume that each word is independent (a patently false assumption, but nevertheless an important simplification of the problem), then we can combine the probabilities for each word via a simple formula.

Given two independent posterior probabilities p and q, the combined probability is

p*q

----------------

p*q + (1-p)*(1-q)

Here’s the code if you want to see it: spam/bayes.py.

I should note a few deviations from the way i described the algorithm above:

-

First, we didn’t have access to the message bodies - only metadata like the sender, subject, source IP address, and stuff like that. We also had a list of “spam rules” for each message, which were features similar to the ones i described above like whether the message contains an image, whether it contains a url, etc. I assume these rules were hand-picked for relevance to spam hunting.

-

I calculated not only the probability of spam, but also the probability of ham. This was one of the insights from the SpamBayes project: by computing these two probabilities independently, you gain the ability to classify not only spam or ham, but also uncertain email. Email which has a high spam probability as well as a high ham probability is likely to be a borderline case that even humans have difficultly judging. Like a corporate newsletter for example. Some people might want it, some people might not; it’s difficult to classify for certain.

-

Instead of setting an absolute cutoff percentage for labeling something as spam (say, anything with a spam probability of greater than 90%), I simply compare whether the spam probability is greater than the ham probability. If it is, i say the message is spam, if not, ham.

There is actually some deep scientific reasoning behind this. When trying to determine the truth of a hypothesis, it makes absolutely no sense to try and calculate the absolute probability of it in isolation. It’s impossible. The only thing you can do is ask if this hypothesis is more likely than the competing hypotheses.

So what we’re asking is, does the hypothesis “this message is spam” fit the data better than the hypothesis “this message is ham”? If the spam probability is 5% and the ham hypothesis is 0.1%, then it is 50× more likely that the message is spam rather than ham, even though both probabilities are small in absolute terms.

-

Finally, I used Laplace smoothing in computing the word probabilities to avoid biasing my algorithm with pathological cases where a word appears exclusively in ham or spam messages, or doesn’t appear in any messages.

Results

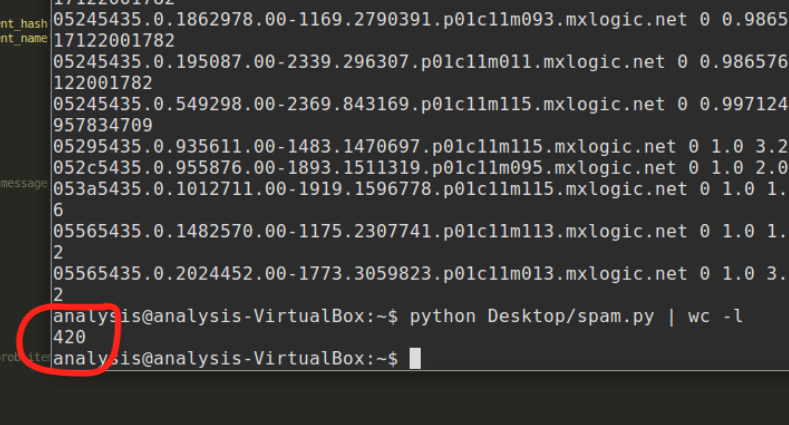

By training my Bayesian filter on the full database of 100,000 messages,

i was able to flag messages correctly except for 420 cases,

which is an accuracy rate of more than 99.5%. \o/

This, of course, is cheating, because you aren’t allowed to verify your algorithm on the same data set you used to train it. (Doing so is prone to overfitting and doesn’t give an accurate picture of how the algorithm really performs.)

So let’s try again.

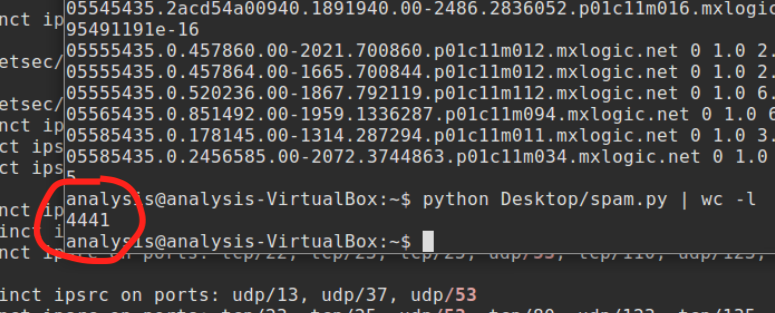

After modifying the code to only train on a random sample of 50,000 messages

(half of the full database),

the number of misclassified messages skyrockets to about 4,500,

for an accuracy rate of about 95.5%. /o\

This is not fantastic, but is still competitive.

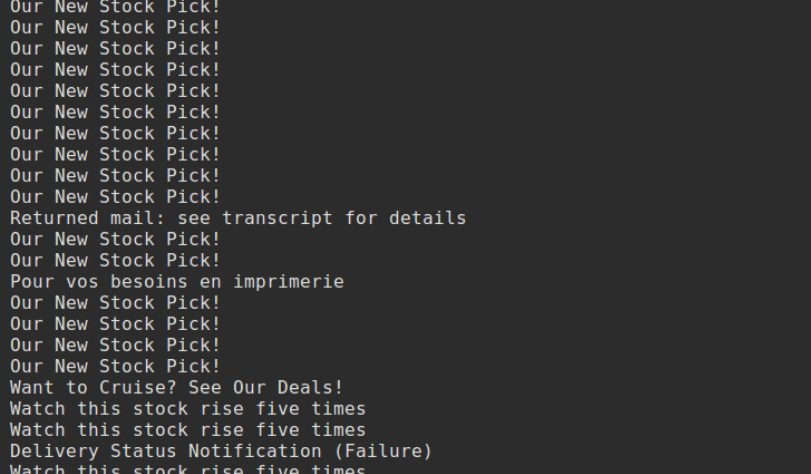

In the recorded lectures, the class divided into three groups to try and classify the spam messages.

I want to repeat some of their methods here.

-

The first group got a large number of messages by flagging messages with the subject “Our New Stock Pick!”, and then looking at which IPs sent those messages and blocking all messages from those IPs.

In effect, they created a post-hoc IP blackhole list.

-

Another group used the attachment hash. I turns out that 63,000 of the messages have the same attachment, which is kind of a dead giveaway that something isn’t right. They also blocked the Stock Pick subject line, but didn’t trace it back to IP addresses. This group was very careful to avoid false positives, with only one confirmed false positive.

-

The third group used the attachment hash, and blocked a bunch of known bad sender addresses.

Lessons

-

Although my Bayesian algorithm fared well, I have no idea how it worked. I don’t know what features it thought was important and which it dismissed.

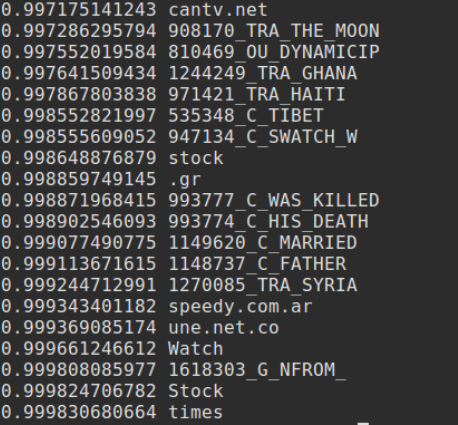

…Actually, I guess I could just see which words have the highest spam probability.

There they are. They aren’t necessarily the words which flagged the most spam, – which would also be interesting. The

ODD_CAPTIAL_WORDSare from the presupplied spam rules I mentioned above. Also, I actually filtered out all words with a probability of 1.0, which were all weird hex things. I’m not sure what those were from. Maybe the attachment hash? -

The point is that I didn’t develop any intuition for what sorts of red flags to look for because I delegated all of the thinking to the algorithm.

-

The Bayesian approach performed remarkably well for how simple it is. It performed less well tested under fair conditions, true, but still not horribly. It certainly wouldn’t compete with a state-of-the-art solution, but I could definitely see it being a component of one.

-

Because I assume all words in a message are independent, the algorithm will not be as accurate as it could be. It also can’t recognize phrases like “Stock Pick” as being different from “stock” and “pick” appearing in unrelated sentences. This means that it might have trouble picking out higher-level patterns in the data.

-

I also don’t think it would be clever enough to do the thing that the first group in the recorded lectures did where they tracked a spammy subject line back to all the IPs that sent it. It might detect that certain IPs were more closely associated with spam, but i don’t think it could do anything further with that information. This goes back to the point about recognizing higher-level patterns.

-

Training the Bayesian filter relied on having access to a horde of spam and ham messages that had already been classified. You wouldn’t be able to use this approach if all you had was unclassified messages.

-

I did absolutely nothing to try and minimize false positives.

Acknowledgements

This post is based on lectures given by Eric Peterson, Research Manager at McAfee.