Week 7: Web Security

Welcome to week 7 of this series. Astute readers may notice that the last post was week 5. What happened to week 6? Well, it was kind of dull so I decided not to blog about it. You’re welcome.

This week we’re talking about web security.

Web security is important because more and more of our daily lives happen on the web – you probably check your bank account online, for example.

Traditional software is fading away and being replaced by web apps. Browsers are subsuming more and more of the capabilities of the operating system, leaving apps with less incentive to go native.

(It’s hilarious to watch browser vendors relearn UI lessons that desktop OSs learned decades ago. Things like modal dialogs and window management are being painfully reinvented and rediscovered.)

This isn’t limited to just legitimate programs – some modern malware doesn’t even try to leave the browser either. It’s happy to just live in your browser and sniff all your web traffic and not even go to the effort of trying to leverage a browser exploit to leap onto the underlying OS. This has advantages for avoiding detection – as i believe we touched on earlier, most antivirus software is based on file scanning. If a piece of malware exists only on a webpage, there’s no file on your computer to scan.

The browser

When we say “web security” we basically mean “browser security”. Modern browser are complex beasts that bear little resemblance to their primitive ancestors. Dealing with modern web content requires ever more complicated JS engines, CSS engines, etc. New standards like HTTP/2 and WebAssembly come out every year.

Browsers are adding an enormous amount of complexity, which leads to an ever greater attack surface. To control that attack surface, browsers have to implement layers of security measures.

Things like

- sandboxing / isolation of tabs

- same origin policy to protect web pages from each other

- url reputation to block known malware sites

- url scheme access rules

I’m sure we’ll see even more layers added on over the years. Even now there are experiments with placing each tab into a separate VM environment.

When we think of securing the browser, we usually think of defending it from the web. But we can’t overlook the threats from the other side – programs that attack the browser from the OS.

-

Toolbars. I remember a time when everybody was trying to get you to install their toolbar for Internet Explorer. Many of these toolbars are less than helpful. I think the Java installer still bundles the Ask Jeeves toolbar.

-

Flash and Java were (are?) popular vectors for attacks. You also get things like the WebEx plugin, which has had vulnerabilities in the past.

-

Antivirus programs will often try to inject DLLs into the browser to let them intercept and scan web traffic. Reportedly, the Chrome team deals with a lot of bugs caused by AV vendors injecting code into Chrome. Tavis Ormandy of Google’s Project Zero seems to spend his time exclusively finding embarassing security vulnerabilities in so-called security tools.

- Lenovo famously shipped a bit of software called Superfish on their laptops in 2015, which installed a rogue root SSL certificate that could be abused by attackers to issue themselves a valid SSL certificate for any domain.

Thankfully browser vendors have started to push back against this sort of behaviour by blocking known vulnerable extensions and plugins, and generally making it harder for programs to modify the browser without the user’s knowledge and consent.

User security

One of the best ways to attack the web is not to attack the browser but go directly to the user – social engineering.

I won’t cover every social engineering method here. You already know what phishing is, for example.

Here are a couple of the more interesting ones we discussed:

-

SEO poisining. Malware sites seed themselves with popular search terms, hoping to get to the top of the results for that search. How many times have you mindlessly clicked the top result, assuming that it was a legit site? When some random blog accidentally got placed at the top result for “facebook” a few years ago, they got a wave of confused users wondering why Facebook had suddenly changed their look so drastically and removed all their social features.

-

Robin Sage was a fake profile that a security researcher created online to demonstrate social media attacks. The idea is to try to befriend people who work for whatever company you want to target and either use them to get closer to your target, or try and get information from them.

- Malvertising. This is the one that keeps me up at night. Malware authors use ad networks as a delivery mechanism for javascript malware. As far as I’m concerned the existence of malvertising is the best argument for using an ad blocker.

Application security

The third way to attack the web is to go through vulnerable web applications.

SQL injection

We discussed SQL injection. I don’t have anything to say here that hasn’t been covered to death already by a million of online tutorials. No modern web apps should be vulnerable to SQL injection. Use parameterized queries.

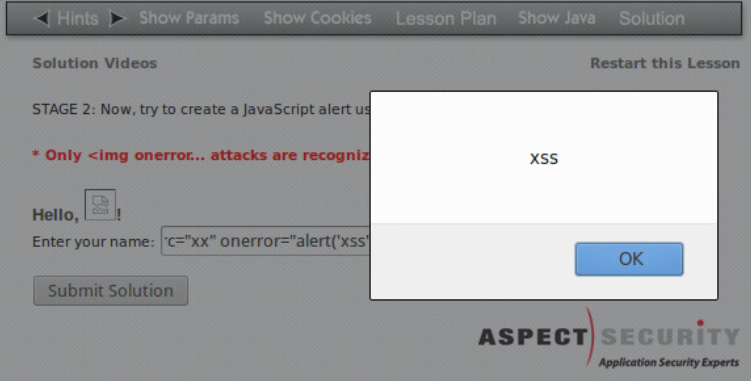

XSS

We also discussed XSS, briefly. This is the same category of attack as SQL injection: someone pasted user input into raw HTML without escaping it.

If you want to avoid SQL injection, XSS, and this entire class of vulnerability, read this and internalize it:

A common suggestion is “sanitizing” your input. If someone tells you to do this, punch that person in the face […]. If you sanitize input, you will almost certainly fuck up legitimate data and still miss a few edge cases. Evil data doesn’t need to be “de-eviled”; it needs to be passed across interfaces safely. What’s an interface? Anywhere two different layers stick together. There’s an interface between your program code and your SQL. There’s an interface between your Web server and your program. There’s an interface between your data and the HTML you generate. Anytime two systems interact, data needs to be transformed from one to the other. The most common security problems arise because the programmer figures “well usernames are just letters” and dumps some mystery data directly into a template or query or whatever.

Web goat

If you want to play around with web exploits yourself, maybe check out the web goat - an intentionally vulnerable tutorial-type program that walks you through exploiting a variety of common vulnerabilities, including XSS and SQL injection.

On the other hand, it’s written in Java so maybe pass.

SQLiX

It turned out that the lecturer this week was one of the authors of SQLiX, a perl program for automatically exploiting SQL injection bugs. It can do crazy things like identify the type and version of the SQL server that is running (i.e. MySQL, SQL Server, etc) and perform blind SQL injection, which is where you are able to execute arbitrary SQL code but can’t see the results – the trick is apparently to exfiltrate the data one bit at a time based on whether you trigger an error or not.

URL classification

Browsers and AV products will try to block malicious URLs. How do they know which URLs are malicious? URL classification!

(Okay, browsers check against a blacklist of known bad sites, but where do you think the blacklist comes from?)

We dipped our toes into URL classification in class this week. Specifically, content-agnostic URL classification, where we look only at the URL and not actually at any of the page content.

How does this work? It turns out that malicious URLs have a lot in common. For example, most phishing sites try to make their url look similar to the target site in predictable ways

e.g.

eu.battle.net.blizzardentertainmentfreeofactivitiese.com

is a phishing url for blizzard’s battle.net.

When trying to come up with rules, my main goal was to avoid false positives. False positives are a big no-no in this sort of automated scanning because of the “boy who cried wolf” effect – if your security tool constantly flags benign sites as dangerous, users will learn to ignore it, or maybe even disable it entirely.

I adopted a basic approach of calculating a score for each URL that was the sum of lots of different features. Each feature was worth a small number of points, usually 1 but sometimes more for strong indicators. Positive features lowered the score and negative features raised it. At the end, i treated any URL with a score of 1 or more as malicious (this cutoff means that we need to see at least one suspicious feature for a domain to be flagged – we start off by assuming good intentions).

You can check out my efforts here: https://github.com/magical/cs373-urlclassifier.

I’ll go through some of more interesting features.

-

One good indicator is the domain age: malware sites tend to be short-lived; they pop up one day and are gone the next. If a domain was registered in the last 10 days, that’s more suspicious than a domain that was registered over a year ago.

-

I also added a rule which gave a boost to well-known tlds like .com, .net, .org, and gave a penalty to tlds like .ru (Russia) and .vu (vanuatu). This is dangerous territory because now we’re discriminating based purely on the country that a domain was registered in – a very weak indicator. Yes there are lots of spam domains with a .ru, but there are plenty of legitimate .ru domains as well.

One reason this works is that people browsing in the US will rarely if ever visit a Russian domain, even a legitimate one. But presumably people living in Russia visit Russian domains more frequently; that is, we can expect statistics about TLD frequency to vary by country.

-

Domain names which had .com or .net as a subdomain component were almost certainly phishers trying to pass off their URL as some other site – see the battle.net example above.

-

Alexa rank is an astonishingly good indicator of a domain’s maliciousness. Alexa basically ranks website popularity. A low rank (<100) means that a lot of people visit it, and this is a good sign that it is not malicious; whereas a non-existent or very large rank (>20000) means is a good sign that a url is malicious. It’s not a perfect metric of course – historically the rankings have relied heavily on stats collected from users with the Alexa toolbar installed – but it performs very well. The non-existent ranking rule flags around 300 malicious websites in the training set, with very few false positives.

-

URL length is an okay indicator. Some types of attacks rely on feeding a legitimate but insecure site bad query parameters, for example, which inflates the URL length. Other times phishers will try to obsfuscate the url with a bunch of garbage.

It also picks up some false positives, unfortunately. Plenty of legitimate sites have ugly longass urls, e.g.

https://d262ilb51hltx0.cloudfront.net/fit/t/1200/960/gradv/29/81/55/1*tbk3Xr3EK1jJv8RaN9RQ-A.jpeg -

I blacklisted certain words what phishers seemed to target a lot. “paypal” and “googledocs” seemed to be common targets,

-

Similarly “wp-admin” and “wp-includes” showed up a lot in hacked wordpress installations. Those got blacklisted as well.

-

I blacklisted

.phpfiles. Fight me.

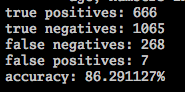

Here’s my final score on the training data:

Accuracy is the percentage of URLs that were correctly identified –

that is, (true positives + true negatives) / total.

Given more time, i’m sure i could have caught more malicious URLs, but I’m pretty happy with where i ended up – particularly the low number of false positives. An accuracy of 85% with almost no false positives is nothing to sneeze at.

Here are all seven of them:

false positive (1): http://mycountdown.org/countdown.php?cp2_Hex=f5f5f5&cp1_Hex=15c277&img=&hbg=1&fwdt=200&lab=1&ocd=My%20Countdown&text1=happiness&text2=Tanner%20arrives%20in%20Florida&group=My%20Countdown&countdown=My%20Countdown&widget_number=3010&event_time=1402079400&timezone=America/New_York

false positive (1): http://imp.ad-plus.cn/201306/eba44fc619ecd77b081a37b2a9bc9d6f.php?a=99

false positive (1): http://js.app.wcdn.cn/ops/game/js/signup/upgrade/toUserUpgrade.minlist.js?v=201310161321

false positive (2): http://s.kaixin001.com.cn/js/_combo/seclogin,apps*common*AQqLogin,apps*common*AOauthLogin-004835e68.js

false positive (1): http://cms.singtao.ca/publish/counter.php?Id=5005037

false positive (1): http://nspt.unitag.jp/c906999ddcc53ef2_576.php

false positive (2): http://img.uu1001.cn/x/2010-07-22/18-06/2010-07-22_aac7845bbc6ce5cf1b945ebac8f29ff4_0.xml

They mostly ran into a combination of a low Alexa rank, use of PHP, and some other indicator.

I don’t know about you but i’m happy to accidentally flag ad-plus.cn as malicious.

And actually, they are all old domain names (a weak indicator of non-maliciousness). By tweaking the weight associated with that heuristic, i was able to get the number of false positives down to just two.

Acknowledgements

This post is based off of lectures given by Cedric Cochin of McAfee Labs.