Week 5: Rootkits

This week we dive into windows internals to learn about rootkits. This is going to be a shorter post this week because i’m burning myself out writing these.

Hooking

Once a piece of malware has gotten onto your system, as we discussed in week 3, one of its primary goals is to blend in or hide.

The malware we’ve seen so far has tried to blend in by choosing names which could plausibly sound like system process; or tried to hide its actions by deleting its installer files and trying to keep a low footprint on the machine.

But the other way to hide is to trick the operating system into lying about what’s on the system. If you can’t see the malware process running in process explorer, and you can’t see its files in on the filesystem, and you can’t see any of its registry keys, it might as well not be there.

We call these programs rootkits.

The primary method used by rootkits to hide themselves is called hooking, which is where the rootkit replaces some system call with its own code which filters itself out of the results. For example, one of the rootkits we analyzed this week hooked the NtQuerySystemInformation call to hide itself from the process list.

Rootkits primarily run in the OS kernel (at least partly), because the kernel is what’s responsible for giving other programs their view of the world; that the code they need to hook.

There are lots of potential places for hooks. Here are a few:

- System Service Descriptor Table (SSDT). When a system DLL needs to call into the kernel, it goes through this table. Windows looks up the index of the system call and runs whatever function it points to. I think this is similar to whatever structure in the linux kernel maps syscall numbers to handlers.

- IRP table. This seems to stand for I/O Request Packet, which is some sort of structure that Windows uses to keep track of pending I/O requests.

- Interrupt dispatch table (IDT). Every OS has a table of interrupt handlers; when the processor receives an interrupt, it jumps to the appropriate address in the interrupt dispatch table.

- SysEnter/Int 0x2E. SysEnter is the instruction on x86_64 CPUs for making a system call. INT 0x2E is what windows used on 32-bit CPUs, before there was a dedicated instruction for it. (Linux used INT 0x80). If a rootkit can hook the syscall mechanism, it can intercept any and all system calls.

Tools

Before going any further, let’s take a break to talk about tools. The problem with a rootkit is that it runs in the kernel, so if you want to be able to poke at it and debug it, you have to be able to debug the kernel.

-

LiveKd from Sysinternals is a live kernel debugger with a command-line interface similar to WinDBG. It allows you to peek at kernel memory from inside a running system. There’s a huge caveat though: you can’t change anything, and you can’t pause the kernel to step through things. In other words, it is a read-only view of the system. It can’t write.

-

WinDBG remote allows you to attach WinDBG to a running kernel on another system. This gives you the full power of a dubugger, including the ability to pause the program, step through instructions one-at-a-time, and change memory to your heart’s content. The reason it has to be remote is that when you pause the kernel, you pause the entire system. You can’t interact with a system at all while it is paused. One way to set this up is to run two VMs with a virtual serial connection between them. Another way, presumably, is to run two physical machines with a physical serial connection between them.

-

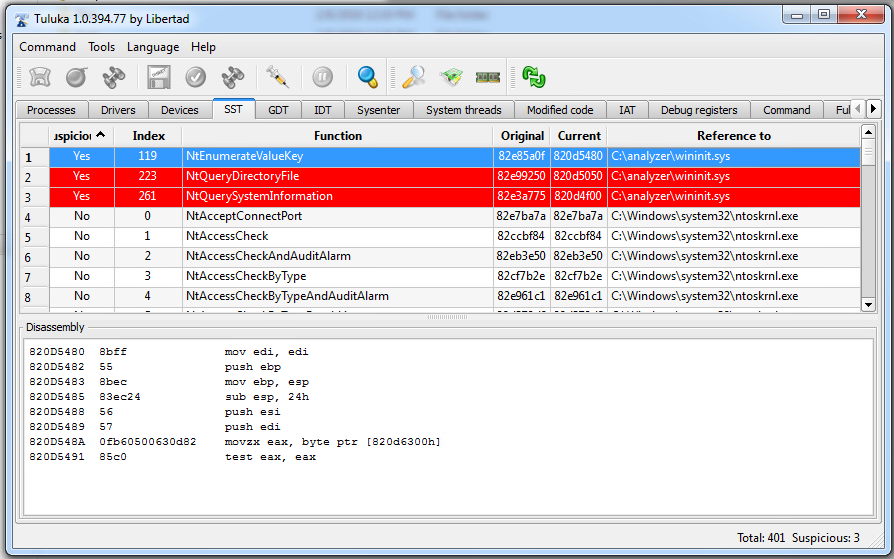

Tuluka is a handy little program which looks for known tricks that rootkits play, like hooking the SSDT table, and flags suspicious entries.

-

Process hacker is like Process Explorer, but it allows you to read and modify a process’s memory. And other things.

Agony

We explored SSDT hooking in great depth by analyzing a rootkit called Agony.

Here’s a screenshot of the SSDT in Tuluka.

The three red rows (er, including the highlighted blue one)

have been modified to point and now point to code in

C:\analyzer\wininit.sys.

If we look for C:\analyzer\wininit.sys in Explorer or the command prompt, it

doesn’t seem to exist –

that’s because Agony has hooked the NtQueryDirectoryFile call,

which is responsible for enumerating the contents of a directory.

Agony’s hook calls the original NtQueryDirectoryFile,

filters out the wininit.sys entry,

and returns the modified list.

This is a general pattern:

pretty much any rootkit that doesn’t want to totally break the system

has to eventually call back to the original system call.

(Can you imagine how much chaos it would cause if all files on the system

were invisible? I doubt you’d get past the boot screen.)

This means that the rootkit has to remember the original value of the SSDT

entry and store it somewhere in memory, which we can find by setting a breakpoint

on the hook function address and tracing it until the rootkit makes

a call back to the original function.

Once we have that, we can patch the SSDT entry back to its original value and

watch as wininit.sys mysteriously appears in file explorer.

Userspace hooking

Although I said rootkits usually infect the kernel, it’s actually possible to hook entirely in userspace (provided you’re running in kernel mode or with admin permissions so you can write to other processes’ address space).

How does that work? Well, when an executable is linked with a DLL – like, say, KERNEL32.DLL – any calls it makes to functions in KERNEL32.DLL are actually compiled into an indirect call like

mov esi, dword ptr [notepad!_imp__SendMessageW]

call esx

And somewhere in the exe there is a table of function pointers

for _imp__SendMessageW and all the other calls it makes to that DLL.

00bd001234 notepad!_imp__SendMessageW dd 00000000

00bd001238 notepad!_imp__SetFocus dd 00000000

and so on

When the program is loaded by the OS, the dynamic linker goes through and fixes all these function pointers to point to the actual addresses of the functions in KERNEL32.DLL (or whatever).

So! To hook these calls, all the rootkit has to do inject itself into the target program and overwrite these addresses to point to the rootkit’s malicious version of the function, similar to the SSDT table except it has to be done for every program instead of just once in the kernel.

Bootkits

Bootkits are even lower-level than rootkits. Rootkits attack the kernel, but bootkits go one step deeper and attack the bootloader. Since the bootloader runs even before the operating system kernel gets to run, this gives them even more control over the system.

It also helps them hide better, just by virtue of the fact that the malicious code is stored in the master boot record rather than a file in the filesystem, making it invisible to file-based antivirus scanners.

Boot sequence

- BIOS initializes the hardware

- BIOS calls code in Master Boot Record (MBR) sector of disk 0

- MBR loads bootloader from boot sector of the active partition

- bootloader run second stage bootloader from filesystem

- second bootloader does some stuff, presents a boot menu, whatever

- second bootloader hands control to the OS kernel

Bootkits can infect pretty much any one of these steps, but it’s pretty common to see them infecting the MBR.

The MBR consists of code, followed by the master partition table, followed by

the marker FF AA.

An MBR bootkit will typically copy sector 0 to some other unused sector

and write its code to sector 0.

With VM support, WinDBG can actually attach early enough in the boot process to step through the MBR code, which is pretty cool.

Now that MBR is being phased out in favor of GPT, I’m not sure where that leaves bootkits. We’ll probably see more malware that infects the UEFI.

Homework

We were given a challenge this week to write a program that could enumerate all running processes, threads, modules (DLLs) in a process, and memory pages in a process.

I found two different Windows APIs to do that: PSAPI and “Tool Help”.

PSAPI is a windows library for manipulating processes. From what I can tell, it can enumerate processes and modules, but not threads.

Tool Help is a library which grew out of an earlier set of 16-bit APIs which provider helpers for debugging tools (hence “tool help”).

It uses a snapshot-based approach in which you call Createtoolhelp32snapshot and then functions like Process32Next to traverse the snapshot.

This offers a more coherent view of the system, but is also a lot slower.

There are also low-level calls like NtQuerySystemInformation, but these are

either not documented, or documented as being unstable.

Acknowledgements

This post was based on lectures given by Aditya Kapoor of Intel Security.