Week 3: Malware Defense

We’ve spent two weeks looking at malware. First, we looked at how malware works and how to analyze it. Next, we looked at how to gather evidence from a malware attack.

But those are both reactionary - something that takes place after the malware has already gotten into your system.

How can we actively defend against malware? And how can we disinfect a system that has been infected with malware?

Attack Graph

All malware pretty much follows the following stages:

-

First contact.

Malware gets onto the machine somehow. This can be any attack vector, from an email attachment, to a drive-by download in an ad, to a USB stick left in a parking lot.

One particular vector worth mentioning is “watering holes”: if your target is a company, and you know they get software or support from a third party, you might target that third party first.

-

Local execution.

After the code gets onto the machine, it needs to get executed. There are three general ways this can happen.

- Social engineering - trick or coerce the user into executing the code themselves.

- Exploiting a bug - traditional attacks like buffer overflows.

- Exploiting a feature - for example, Windows “autorun” feature will automatically run code on a CD when you insert it.

-

Establish presense.

The malware is executing, but it doesn’t have a permanent presence on the machine. A single reboot can wipe it out in this phase.

The primary danger to malware is that it will be detected and deleted before it gets to stage 4, malicious activity.

Therefore malware needs to blend in or hide to avoid detection, and establish a way to persist.

It can blend in by choosing legitimate-looking filenames like

svch0st.exe, install itself alongside operating system files, change its modified time to match other files, etc.It can hide by infecting the bootloader or operating system itself and lying to programs about which processes are running, or which files exists on the machine. Malware which chooses to hide in this manner are known as bootkits and rootkits.

Finally, it can persist by configuring the system to run the malicious code on startup, or using DLL side-loading to piggyback on another program, or other methods. Malware authors are continuously inventing new ways to get their programs to persist. Here are a couple inventive ones:

-

Malicious activity.

The end goal. Once the malware has established a foothold onto your machine it can do whatever it wants. Whether that’s mining bitcoin or encrypting your harddrive or stealing your credit cards.

Defenses

We can attempt to defend at any of these points.

Antivirus works mostly at stage 2, for example. It blocks malware from executing by scanning every program before it runs and checking if it matches a blacklist of bad programs. We’ll look at how these blacklists are made in more detail in a moment.

There is a technique called “behavioural analysis” that works at stage 4: it looks at what programs are doing and uses machine learning or what have you to decide if programs are acting in a way that is similar to malicious programs. My understanding is that this is still something of a research area.

We can defend at stage 1 partially by educating users, however…

<rant>

I want to take a moment to call out the person in class who immediately suggested “better users” as a malware defense. This is called blaming the user, and it is always a bad idea.

It’s true that you can’t have a secure system without some user cooperation – or rather, you can’t have a secure system if your users actively undermine it. (Security is a property of a complete system, including the users, not a panacea you can just bolt on after the fact.) But! The lesson here isn’t that users can’t be trusted, in fact, users have to be trusted to some extent for a system to work. A lot of attack vectors that we see work even when the user is doing everything they are supposed to do and acting in the best intentions.

As computer security expert Bruce Schneier says,

Users are free to click around the Web until they encounter a link to a phishing website. Then everyone wants to know how to train the user not to click on suspicious links. But you can’t train users not to click on links when you’ve spent the past two decades teaching them that links are there to be clicked.

We must stop trying to fix the user to achieve security. We’ll never get there, and research toward those goals just obscures the real problems. Usable security does not mean “getting people to do what we want.” It means creating security that works, given (or despite) what people do.

—https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2016/10/security_design.html

Stop blaming the user.

</rant>

Defense in layers

The number one lesson here is defense in layers. You can’t rely on a mitigation at a single level to catch all types of malware; rather, try to catch as much malware as you can at each layer of your system, and hope that the stuff you don’t catch at one layer is caught at the next layer.

Yara

Let’s talk about writing antivirus rules!

Yara bills itself as “the pattern matching swiss knife for malware researchers”. Yara is a rule engine similar to the ones used in antivirus software (AV). We couldn’t play with a real rule engine in class because they are all proprietary, so we used yara.

There is an editor for yara, although it looks unmaintained, and honestly it doesn’t do much.

The syntax of yara goes something like this:

rule rulename {

strings:

$a = "malware"

$b = { 12 34 56 ab }

$c = /[Aa]nti[Vi]rus/

condition:

$a and $b or $c

}

The strings section defines patterns to match. Patterns can be strings, hex strings, or regexes. Hex strings can have wildcards. Regexes are… regexes.

The condition section defines an arbitrary boolean expression using the variables defined in the strings section.

There are other sections, and other features. For complete documentation, check the yara website.

The zen of writing AV rules:

- smaller rules are better

- be precise

- but not too precise

- don’t flag OS files

Let’s see how to use yara to match a couple malware samples.

Sample 1

The first set of samples is from a piece of malware known as Sytro.

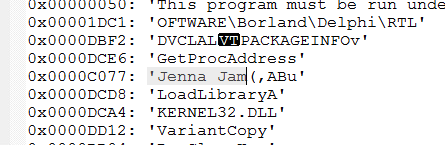

I opened these files up in a strings viewer and, after a little while, noticed that the string “Jenna Jam” occurs in a couple of the executables

Let’s try that.

Turns out it identifies all the samples!

I also tested the rule against the files in C:\Windows\System32 to check for false positives.

I didn’t find any. Good.

Turns out that I got lucky - the full string is Jenna Jameson, but the executable I looked at first was packed with UPX, so the ending got garbled.

We can tell it was packed with UPX by the appearance of the string UPX0 near

the beginning of the file.

I think I would want to search around for a string that is more “actively malicious” in the malware to pair the Jenna string search with, if this were a real case.

Note: a real antivirus engine would just unpack the file first before scanning it, rendering this problem moot.

The rule I ended up with was

rule Sytro {

strings:

$jenna = "Jenna Jam"

condition:

$jenna

}

The instructor did the same thing but also added another string

rule Sytro {

strings:

$str40 = "Jenna Jam"

$str27 = "AikaQ"

condition:

$str24 and $str40

}

This is better because there will probably be fewer false positives, but you have to find the string “AikaQ” first, and notice that it is in every malware sample.

Finding common strings like this is a bit difficult and tedious to do by hand, so it would be nice to automate. We can to some extent, and the yara editor has a tool for finding common strings, but these tend to overfit the data points, finding lots of common strings that are unlikely to generalize to more malware samples. So writing these rules still requires some human intuition.

Sample 2

The second set of samples isn’t an executable but are actually HTML pages. They don’t seem to have much in common except that they are mostly vBulletin forum pages, and there is a sketchy ActiveX control at the bottom of each page.

The directory holding the next set of samples is named CVE-2008-2551, which is a pretty big hint.

Per the CVE,

The DownloaderActiveX Control (DownloaderActiveX.ocx) in Icona SpA C6 Messenger 1.0.0.1 allows remote attackers to force the download and execution of arbitrary files via a URL in the propDownloadUrl parameter with the propPostDownloadAction parameter set to “run.”

Here’s the yara rule I came up with:

rule CVE {

strings:

$activeX = "DownloaderActiveX"

$dl = "propDownloadUrl"

$clsid = /c1b7e532.{1,3}3ecb.{1,3}4e9e.{1.3}2951ffe67c61/

condition:

$activeX and $dl and $clsid

}

At first I only had the DownloaderActiveX rule, but to minimize false positives it is better to include the specific CLSID of the ActiveX control that the attack targets.

This one is fun because the malware authors started to try and obfuscate the code, which is why we have to use a regex to match the CLSID.

Cuckoo

Cuckoo is an open source program used by researchers for malware analysis and automation. The cuckoo host runs a guest OS in a VM (usually Windows, but it supports other OSs too) All behaviour of the malware in the VM is reported to the cuckoo host.

Types of data that cuckoo can collect include:

- log of syscalls that programs make

- list of files created, deleted, and downloaded

- memory dumps of processes

- network traffic in pcap dump format

- screenshots

- full memory dump of machine

Lab Report

We were given four different malware samples and asked to

- Determine which samples were malicious and which were benign

- Analyze one of the samples in depth

Let’s go.

I used Cuckoo to collect data about the malware samples. (Since we were running in VMs anyway, we didn’t have the Cuckoo host, just the guest.)

The process was something like this:

- Reset my VM to a clean state

- Copy the malware to the desktop with the name “bad” (this is how Cuckoo determines which file to run.)

- Start Process Explorer and FakeNet (see week 1)

- Run cuckoo - open a command prompt and run

c:\analyzer\analyzer.py - Cuckoo launches the malware and collects data.

- Once the malware has finished running, go to

c:\cuckooand look at the logs.

The most useful files in c:\cuckoo were

c:\cuckoo\logs, which holds the syscall log for each process that the malware created- and

c:\cuckoo\files, which holds a copy of every file that the malware touched

With this process, what did I learn?

- Sample 1 installs a windows input method and deletes itself. Looks suspicious.

- Sample 2 creates an executable at

C:\qulsa.exeand arranges for it to run at startup. Also suspicious. - Sample 3 appears to be relatively benign - some sort of tool for analyzing executables.

- Sample 4 copies a suspicious-looking executable to a temp directory and then deletes itself. Probably malicious.

Looking at the virustotal results for each sample (linked above) confirms my intuition.

A common theme I noticed here is that programs which try and evade detection by deleting themselves are almost certainly malicious.

Let’s take a closer look at the first piece of malware.

Its MD5 hash is 068d5b62254dc582f3697847c16710b7.

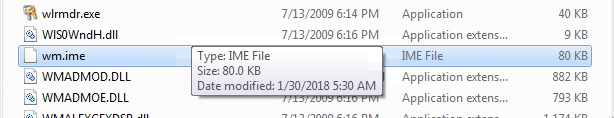

It installs a file named wm.ime to c:\windows\system32\wm.ime and registers

it as an input method.

IME stands for Input Method Editor. They are normally a bit of global UI that allows you to type Asian language characters with a latin keyboard.

Since it installs an input method, I’m guessing that it might be some sort of keylogger.

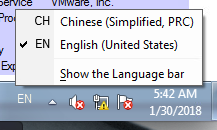

After I installed the malware, I noticed that a little language selector icon popped up in my system tray, with two options: US and CN. I’m guessing that the malware was Chinese, and that it originally targeted Chinese users.

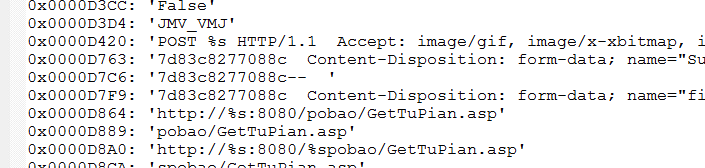

Let’s look a closer look at the IME driver that the malware installs. Perusing the strings with FileInsight, these ones stand out:

POST %s HTTP/1.1 Accept: image/gif, image/x-xbitmap, ...http://%s:8080/pobao/GetTuPian.asp

Now, I’m not expert, but I don’t think a keyboard input method should be making HTTP requests.

Here’s a complete rundown of the actions that the malware takes, based on the cuckoo logs:

- writes to

C:\Windows\system32\wm.ime - reads

C:\Windows\Globalization\Sorting\sortdefault.nls - reads

C:\windows\system32\kbdus.dll - adds an input method E0200804 to the registry

- adds its newly created input method to

HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Keyboard Layout\Preload - writes a batch script to

C:\del30eef.bat

It doesn’t appear to write to kbdus.dll or sortdefault.nls,

just read them, so I don’t think they are malicious.

The batch file simply deletes the original malware executable (“Desktop\bad”)

and then deletes itself. Props to Cuckoo - the fact that cuckoo saved a copy of

the batch script in the cuckoo\files directory made it very easy to analyze;

I would have had a hard time otherwise since it deletes itself immediately.

That’s all I was able to learn about the malware.

Unfortunately, I was unable to catch the malware in the act of making an HTTP call, not was I able to find any log file that it was writing to.

In fact, I wasn’t able to tell if the malware was actually running at all! That’s the pernicious thing about the fact that it was installed as an IME: it’s not a normal executable that you can see in the process list; it’s more like a DLL that gets loaded into other programs.

I tried using Process Explorer to search for loaded DLLs named wm.ime,

but came up empty. I’m not sure if IMEs are loaded like normal DLLs or if they

use some other method.

Regardless, I’ve seen enough to convince me that the sample is indeed malicious, and that it should be removed.

How to tell if you are infected

If you have a file called wm.ime in your c:\windows\system32 directory,

you are probably infected by this piece of malware.

Removal

Delete the file c:\windows\system32\wm.ime.

(Don’t delete the other files mentioned above; you need kbdus.dll to be able to type.)

Open regedit and delete the following registry keys:

\HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\ControlSet001\Control\Keyboard Layouts\E0200804

\HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\ControlSet002\Control\Keyboard Layouts\E0200804

\HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\Keyboard Layouts\E0200804

In regedit, go to \HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Keyboard Layout\Preload and delete the

key with the value of E0200804.

Yara rule

I only have one sample of the malware, so I can’t be sure which strings will be unique to it, or which might vary.

Since the strange URL in the malware is what tipped us off in the first place, let’s use that in the rule. I also check for one of the IME-related syscalls that it uses in an effort to try and avoid false positives in case a legitimate program happens to have a similar URL.

rule keylogger {

strings:

$url = "http://%s:8080/pobao/GetTuPian.asp"

$ime = "ImmGetIMEFileName"

condition:

$url and $ime

}

Conclusion

Pretend there is a nice, tidy conclusion here.

Malware defense is messy? I don’t know.

Acknowledgements

This post was based on lectures given by Craig Schmugar, Research Architect at McAfee.