Weeks 9 and 10: Mobile Security

Hello! This will be the last post in this series. It’s been a fun journey and I’ve learned a lot, and i hope you have too.

This week is about mobile security. Specifically, Android security. We’ll take a brief look at the history of the mobile phone as a platform for malware, review some tools for Android malware analysis, and then dive in for a hand-on look at some android malware.

History of phones

The current big players in the mobile space are Android and iOS. Microsoft also made a bid into mobile with Windows Phone and later Windows Mobile, but recently announced that they were shuttering the project.

It wasn’t always like this — before the iPhone came along, the three big players were Symbian, Palm, and RIM (Blackberry). How times change.

Android

At first Android apps were Java-only; there was no way to write apps that used native code.

Dalvik was Google’s custom implementation of the Java virtual machine, created partially so it could be optimized for embedded devices, and partially to get around licensing issues. (Oracle famously sued anyway.)

Eventually support for native code was added, Dalvik was deprecated, and Android 5.0 finally jettisoned Dalvik support altogether. APK files can still include a classes.dex file to support older devices, but I’m sure even that will fall by the wayside soon.

Android apps are distributed as .apk files.

Anatomy of an APK

An android package is a zip file with a few major components:

AndroidManifest.xml. This is where metadata about the app like its name and icon are defined. It’s also where entrypoints for the app are defined: things like activities (UI screens) and background services.classes.dex. This is an archive of the compiled java codelib. If the app has native code, this is where it goes.assetsis where assets like images go. Notably, a lot of malware puts native executables or other payloads in here under misleading names.

There are a couple others, but these are the ones we are interested in.

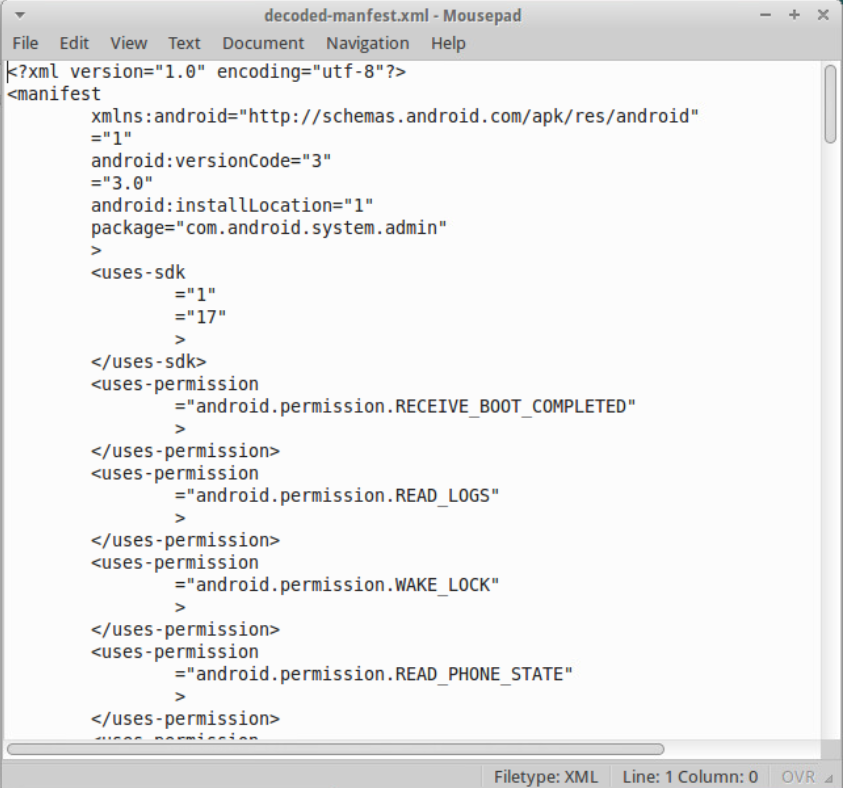

One thing to note about the manifest is that the version stored in the .apk

isn’t actually an XML file. It’s actually stored in a format called binary XML.

You need to use a tool to convert it back into a readable form.

Tools

Static analysis

One of the nice things about Android apps being primarily written in Java is that Java is really easy to decompile. Unlike compiled languages like C++, compiled java code still contains all the identifiers from the original program. Class names, method names, package names, variable names, you name it. Not only that, Java bytecode is higher-level than assembly code, so it is easier to recover control structures. All in all, it’s way easier to recover decent-looking Java code. There are even some good open source tools!

-

apktool is super-useful tool for reverse-engineering android apps. It can extract files from an APK, decode the manifest, and disassemble all the code. And then it can do all that in reverse, building a complete android app from a dissasembled tree. We’ll see that ability come in handy later.

-

JD-gui is an open-source Java decompiler. It’s the most basic of the decompilers listed here, but it’s still pretty good. It wasn’t built for Android analysis though, so you have to massage things back into a format that understands. Speaking of which…

-

dex2jar is a set of tools for converting

.dexfiles to ordinary.jarfiles and back. -

Jadx is another open-source decompiler. The nice thing about Jadx is that it can directly open

classes.dexfiles and APK files. -

JED is a commercial decompiler. It has a lot of tools for analyzing obfuscated code, but it costs a fortune.

Dynamic analysis

- Emulators, emulators, emulators

The Android developer kit comes with a high-quality emulator, since it’s not really reasonable to expect developers to install an app to their phone every time they want to test something.

This is great for us because it gives us a relatively safe environment to test malware out in.

Obfuscation tricks & tools

- identifier renaming

Since Java bytecode stores variable and class names, one of the simplest obfuscation techniques is to rename them all with gibberish names. (This is also a favorite technique for obfuscating source-only languages like JavaScript.)

The Android development kit comes with a built-in obfuscator called ProGuard which performs identifier renaming (and also removes dead code). It isn’t enabled by default, but turning it on is pretty easy.

There’s a commercial fork of ProGuard called DexGuard that adds some more techniques:

- string encryption

- manifest obfuscation

- tricking the decompiler

We’re about to see all these techniques in play.

Obad

Let’s look at an actual piece of android malware.

When it was released in 2014, Obad was called the most complex piece of android malware in existence. Let’s find out why.

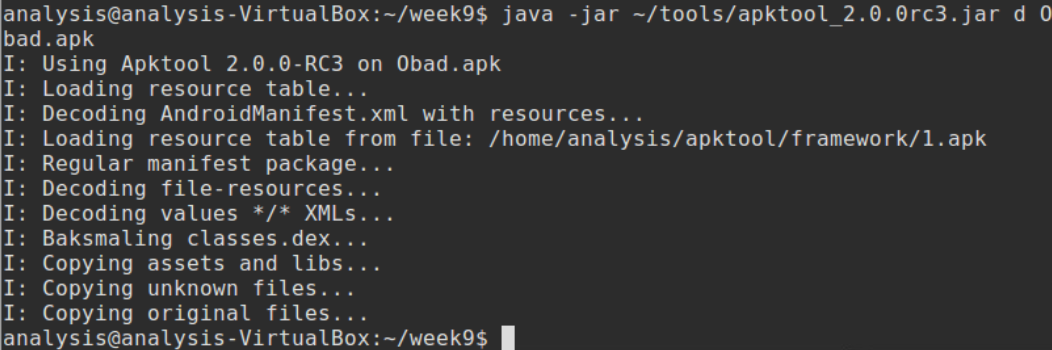

First, we extract the manifest and classes.dex.

That… doesn’t look right. It turns out that old versions of AXMLPrinter, which we used to decode the manifest, had a bug where certain values in the binary XML will make it confused

and print out invalid XML. DexGuard took advantage of this to make manifests like this that can’t be read by the standard debugging tools.

Fortunately this has been fixed in the lastest versions of apktool.

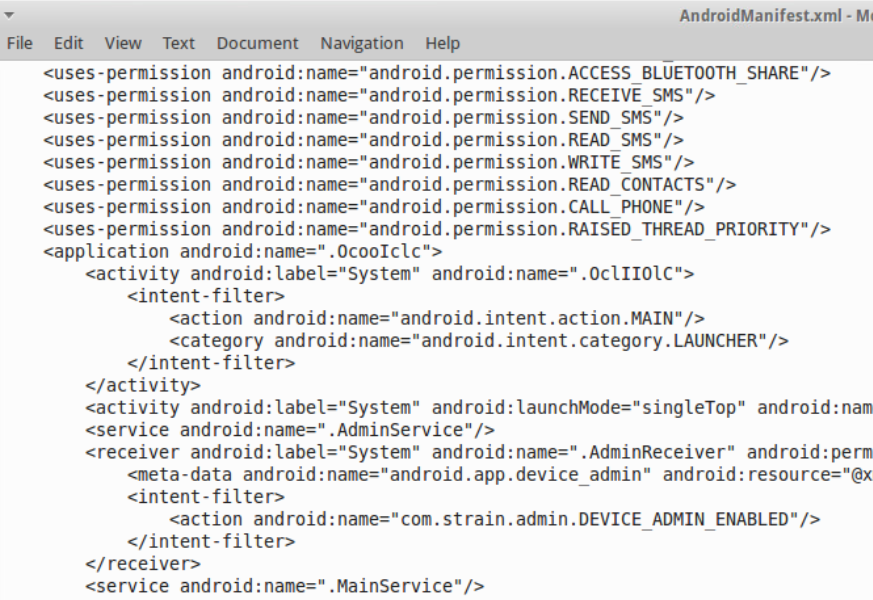

Yeah, that looks better.

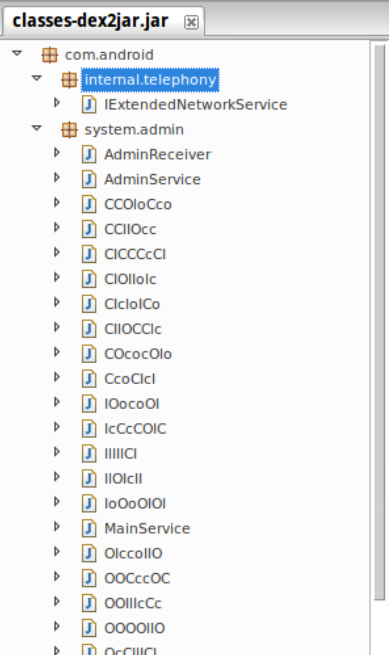

Okay, how about that java code? Let’s fire up JD-gui.

That’s a lot of classes. Here we see the first instance of identifier obfuscation. There’s not much we can do about that with the tools we have at hand, unfortunately, but at least we can read the code right?

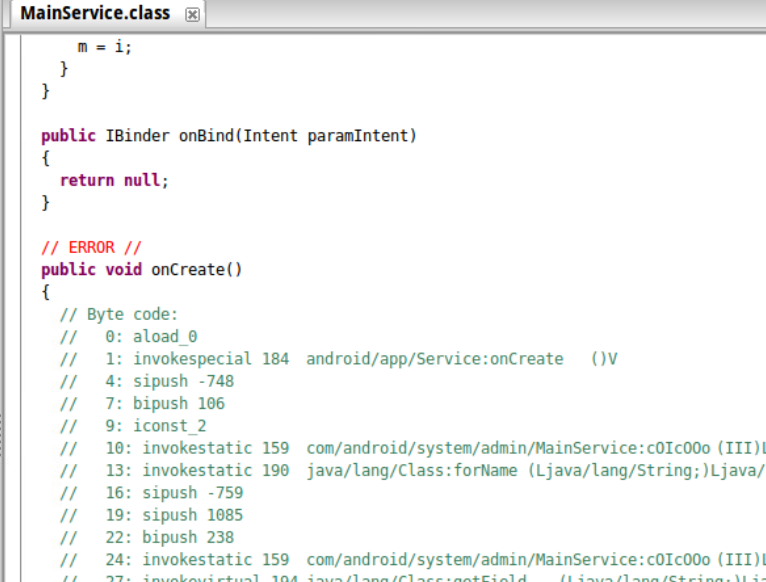

Uh-oh.

We have one trick up our sleeves here.

The reason the decompiler was tripped up because DexGuard had insterted unreachable, junk goto instructions into the bytecode, which threw the decompiler for a loop.

It turns out that we can go in to the assembly code that apktool dumps out, edit out the junk instructions, and rebuild the app using apktool.

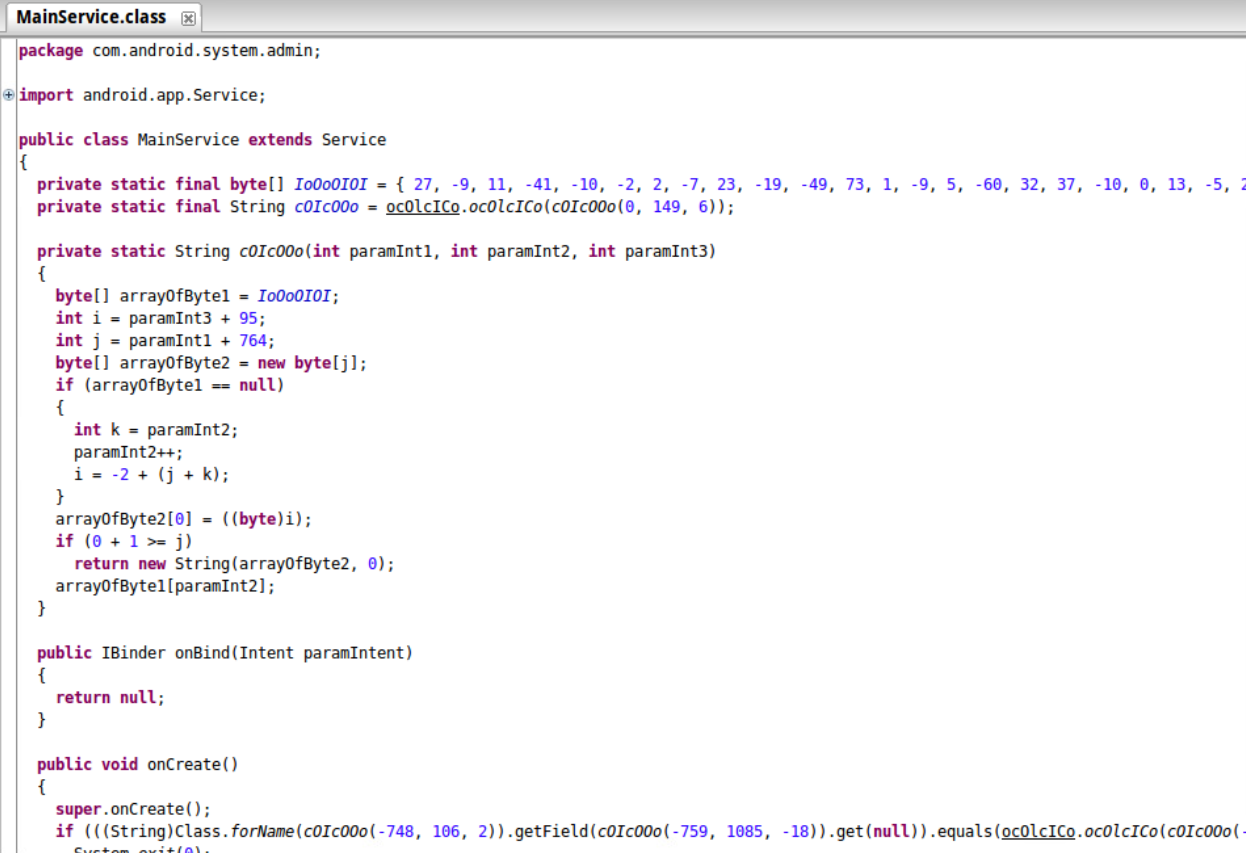

With the junk instructions gone, JD comes through for us.

It’s, uh, not exactly understandable yet, but it turns out that this this happens to be a routine for decrypting strings, which will allow us to understand other parts of the program.

I’ll spare you the rest of the analysis. If you want more detail, check out the writeup i linked above.

Aside from the obfuscation techniques, part of what made Obad so complex was that it was polymorphic - a fancy term in the antivirus industry for malware for which every sample seen in the wild is slightly different, instead of just being an exact copy of the same file.

Obad was polymorphic in two different ways:

-

A unique value stored in a data file. The web server that distributed Obad handed each computer that downloaded the malware a unique copy tied to the particular IP address of the computer that downloaded it.

-

Every day, the obfuscation changed. All the gibberish identifiers became completely different gibberish identifiers.

As you might imagine, this made it very hard to write antivirus rules like we did in week 3 because there weren’t any fixed strings to match against.

Bootkits

I want to briefly talk about Android bootkits. As we talked about in week 5, a bootkit is a type of malware that runs very early in the boot sequence of the computer, before the operating system starts, typically by installing itself in the master boot record or even earlier.

The first known Android bootkit was discovered in 2014

The Android boot process works a little differently than a PC, so the bootkit works a little differently as well.

Oldboot is actually installed as a system process, /sbin/imei_chk,

which is launched on boot by a line the Android boot script, /init.rc

Its payload is an app called “GoogleKernel”. You can try to remove it,

but the bootkit will just reinstall on the next boot if it ever gets removed.

These files are located in the read-only partition of the Android device, where all the other important Android operating system components are found. The only way to remove the bootkit, short of performing a jailbreak, is to reinstall the whole OS.

The most fascinating thing about Oldboot is that it was found preinstalled on certain Android devices from China – and that’s the only known distribution method. It isn’t something that could get infected with on a previously clean device, either your device came with Oldboot on it or it didn’t.

Conclusion

Out of all the stuff we’ve covered, this section is probably the least likely to stay relevant. Ten years ago, Android barely existed and the mobile malware landscape looked completely different. Even as I write this post, most of the Java-based stuff we covered is on the verge of being obsoleted by native apps (or already has), and the rest will probabably be obsolete in another 10 years.

Wrap-up

I want to take a moment to look back and reflect on this series as a whole. In just 10 short weeks we’ve covered

- Malware: basics, definitions and defense.

We looked at how antivirus software works, where its weak points are,

and tried writing our own virus detection rules

- we analyzed the behaviour of some real malware samples

- static and dynamic analysis

- Exploits: how to turn a vulnerability like a buffer overflow into an actual attack

- Forensics: the basics of what a forensic investigator does, and how to recover files and information from a memory dump or disk image

- Rootkits: how they work (hooking) / how to detect and defend against them

- we analyzed a real rootkit

- Web security: we looked at a couple common web attacks and tried our hands at URL classification

- Spam: we looked at how spam messages propaate, and how mail providers automatically flag spam messages and prevent them from reaching your inbox

One of the common themes (although it hasn’t always made it into these posts) has been Social Engineering. I don’t think there was a single week when it wasn’t mentioned in class. Even this week, although I didn’t mention it, a lot of the android malware we talked about were Trojans, which rely on getting the user to infect themselves rather than any sort of security exploit. It seems like the security world is going to be dealing with social engineering attacks for a long time.

Thanks so much for following me along on this journey. I’ve learned a ton and I hope you have too.

Acknowledgements

This post was based on lecures given by Fernando Ruiz of McAfee Labs.